The 1900 Bubonic Plague in Sydney

- Jun 21, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Oct 8, 2025

How Sydney Confronted the Black Death and the Unsung Hero who Oversaw the Quarantine and Disinfection Program

By Alec Smart

In January 1900, bubonic plague came ashore in Sydney and ravaged its way through the harbourside dwellings and inner city suburbs.

The contagion, carried by rats, arrived after a slow but deadly transmission through Southeast Asia, following an 1894 resurgence of the dreaded ‘Black Death’ in Hong Kong. (Now categorised as The Third Plague Pandemic, it actually began earlier in Yunnan, China, in 1855).

After initial public panic and reports of xenophobic attacks on the Chinese community, authorities implemented stern measures to counter the spread of the deadly disease, which reduced its impact.

Bubonic plague is known historically as ‘Black Death’ due to the characteristic blackened extremities of victims, caused by blood seeping from the veins into the flesh, particularly around the nose, fingers and toes - and its catastrophic effect on humanity.

The Second Plague Pandemic that spread across Europe between 1346-1353 killed an estimated 50 million people, half of Europe’s 14th-century population, as well as a third of the population of the Middle East.

Grim effects of the Sydney Plague

It’s a grim disease with a mortality rate between 30% to 90%, depending on how soon it is detected and treated (10% with prompt antibiotic treatment, which was not widely available until the 1940s). Those infected are afflicted with swollen, painful lymph nodes (‘buboes’ – hence the name ‘bubonic’) in the groin, armpits or neck, and experience fevers, headaches and chills.

Lymph nodes are small organs of fatty tissue that are an essential part of the body's immune system. The nodes/glands contain lymphocytes (white blood cells) that aid the body in combating infections and diseases. The nodes filter and trap harmful agents in the blood, including bacteria, viruses, and cancer cells, which are then attacked and neutralised by the lymphocytes.

However, when the lymph nodes are overwhelmed by a harmful bacteria and cease to function, toxins spread throughout the body, causing massive haemorrhaging and failure of internal organs - a painful death.

In an interview published in the 8 March 1902 edition of the Sydney Mail, a ‘medical officer’ described the horrors of contracting bubonic plague. “This medical gentleman said plague was a blood disease, and it attacked a person like a stroke of lightning. A man might be quite well at 6 in the morning and three hours later be very seriously ill with plague. The disease lay dormant in the system from three to ten days, and then suddenly showed itself by bubonic swellings in different parts of the body. This was accompanied by a violent illness comprising high fever and severe pains.

“Plague, unlike many other diseases, did not work in regular stages by the patient first commencing with a slight illness and gradually growing worse. It attacked a man at once, and often in a few hours after the disease had first made itself felt the patient was in a very critical condition. It continued to increase in violence for two or three days, and if death did not take place before the end of the fourth day there was a better chance of recovery. The chief organ affected was the heart.

"The cause of death was generally failure of the heart consequent upon poisoning of the blood.”

Rats carry contagion

The 1900 bubonic plague entered Sydney via Darling Harbour on fleas carried by ship rats (black rats of the species Rattus rattus). Once in the community, it spread quickly, primarily via brown rats (aka sewer rats of the genus Rattus norvegicus) that were rife in the overcrowded harbourside slums, attributable to poor management of garbage disposal.

Authorities oversaw a massive extermination of an estimated 100,000 rats throughout the city, which also included eradication of native bush rats Rattus fuscipes. The city’s bush rat population has never recovered to return to the harbour foreshore environs, which are now completely colonised by the two invasive species.

Within eight months, the 1900 plague claimed over 100 fatalities across Sydney, many of whom were buried in the Third Quarantine Cemetery on North Head (which was established in 1881 for victims of a smallpox epidemic).

First casualties of the Sydney Plague outbreak

The first confirmed case of the 1900 bubonic plague epidemic in Australia was reported on 15 January in Adelaide. A sailor named W. Eppstein ‘absconded’ from the Royal Navy ship Formosa at Port Adelaide in late December 1899. Upon admission to the hospital on 1 January, he revealed he had been ‘lying ill under a tree at Gawler for a fortnight without food before he was sent to Adelaide’. He died within the fortnight.

The first reported case in Sydney, on 19 January, was Dawes Point resident and Central Wharf delivery worker Arthur Paine, who resided at 10 Ferry Lane overlooking the Walsh Bay docks. He, his wife and three children, a servant girl and a female friend who was visiting, were quickly isolated from the community.

They were taken to the Quarantine Station infectious diseases institution on North Head (established 1832, although the remote bushland site was utilised to control the spread of diseases from the 1820s).

Paine, who only showed ‘mild’ symptoms, made a full recovery and was released on 18 February, however, just four days later, the first recorded fatality from the dreaded plague in Sydney was that of sailmaker Captain Thomas Dudley. The Herald reported he was probably infected whilst removing five dead rats clogging the toilet of his first-floor dwelling, which they’d enteredby climbing up defective sewerage pipes. He died on February 22 at his home in Cambridge Street, Drummoyne, and was buried at the Third Quarantine Cemetery on February 24, with the body wrapped like an Egyptian mummy to alleviate public fears over whether the corpse was contagious.

The Herald revealed that “the removal and interment of the body of Captain Dudley were attended with every precaution that was necessary to prevent the corpse becoming a source of infection. It was considered a fortunate circumstance that his residence was accessible by water...

“The space in the coffin not occupied by the body was filled with a very strong disinfectant. Next, the coffin was enveloped in a succession of sheets, which were saturated with disinfectant. Then a jacket of sailcloth was wrapped around the chest. The coffin was removed on Saturday evening to North Head, being towed in a skiff by a launch.... The grave, which is officially known as No 48, was of unusual depth. The coffin was committed to the earth with all its numerous wrappings undisturbed.”

Fleas a vector

The anxiety concerning the enshrouding, removal and burial of Captain Dudley’s corpse was misplaced. The primary vector of bubonic plague is bites from fleas, Xenopsylla cheopis, which transmit it from infected rats.

(Xenopsylla cheopis aka the Oriental rat flea, is distinct from the common flea found on dogs or cats Ctenocephalides canis or Ctenocephalides felis, although there are three other species of rodent fleas that transmit bubonic plague: Northern rat flea Nosopsyllus fasciatus, Ethiopian rat flea Xenopsylla brasiliensis, and European mouse flea Leptopsylla segnis.)

In contrast, pneumonic plague is spread by inhaling droplets of the same bacteria, Yersinia pestis, from infected people and animals, typically spread through their coughing.

However, world medical experts in 1900 were still uncertain of the transmission of the deadly contagion, which authorities realised had little impact on family pets, and thus encouraged dog owners to utilise their canines to kill rats.

In earlier eras, this ignorance saw inspectors, medics and corpse gatherers wear face masks with circular glass eye ports and long bird-like beaks filled with aromatic herbs when handling the victims. This was because they feared inhaling the contagion whilst being in close proximity to the deceased, not realising transmission was via flea bites or coughing.

Thankfully, Dr Ashburton Thompson, President of the Board of Health in charge of countering the plague, was influenced by French physician Paul-Louis Simond, a distinguished scientist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. Simond, whilst testing a new antiserum in Karachi combatting a plague outbreak in India, observed and reported that fleas transmitted bubonic plague between rats and also on to humans.

However, Simond’s 1898 report, La Propagation de la Peste, was not widely accepted by the scientific community until 1907.

In a January 1900 interview, Dr Thompson said, "The popular notion regarding the bubonic plague is that it is dangerous to come within a stone's throw of a patient, but this is an absolute mistake…. Nurses or doctors who take the disease are few in number, and mostly contagion is received because of wounds in the hands when making a post-mortem examination of the body of some person who has died of the disease.”

Rat reduction to combat the spread of the plague in Sydney

The new realisation that fleas were responsible affected how Australian health authorities, supervised by Dr Ashburton Thompson, dealt with the outbreak, ultimately resulting in relatively few fatalities.

These measures, utilising the Public Health Act of 1896, included: intensive cleaning and disinfection of neighbourhoods; the demolition of unsanitary buildings, such as temporary shelters; restrictions on the movement of vessels around the harbour and along the coast; compulsory quarantine of the infected and those whom they came into contact with; closures of libraries and public buildings; and the aforementioned mass extermination of rats.

In a report dated 26 February 1900, the Herald revealed, “The health authorities urge, with a view to preventing the spread of the bubonic plague, that an active campaign should be prosecuted in order to destroy as many rats as possible.”

In March 1900, squads of rat-catchers were formed from a team of 3,000 recruits, and by August an official figure of 44,000 rats were killed and incinerated in an attempt to stop the plague’s spread. Councils paid six pence per corpse, so vermin extermination became a lucrative enterprise, especially among children, who took the rodent corpses to an incinerator in Bathurst St. or dedicated disposal points.

Disinfection and inoculation

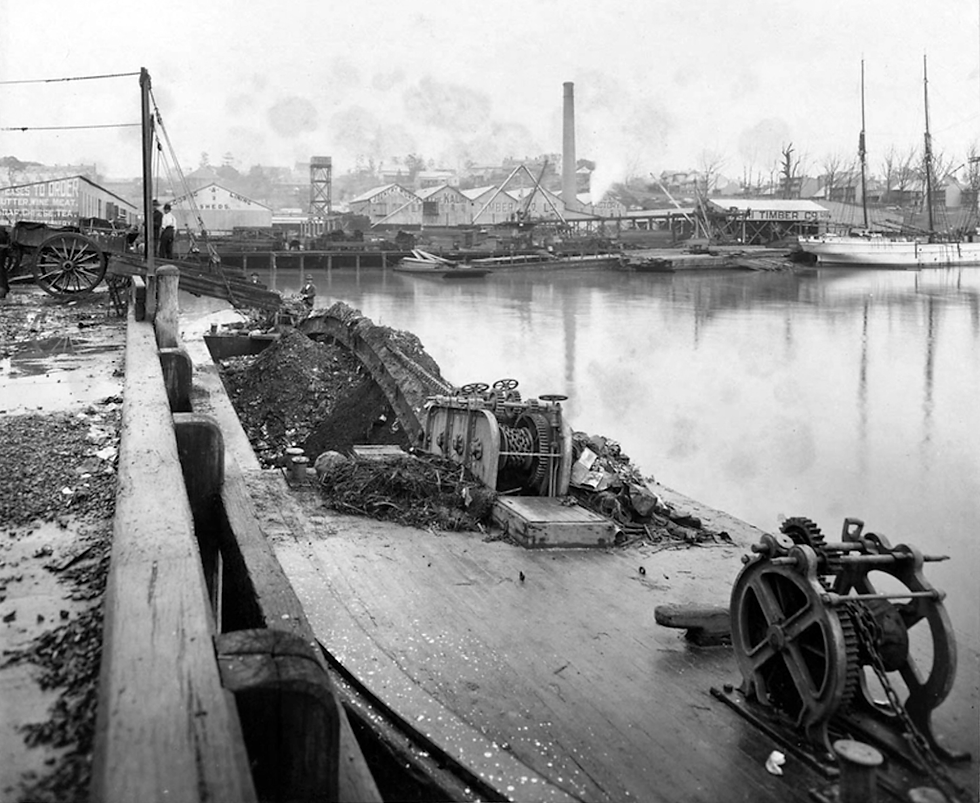

Under the newly formed Plague Dept, specific neighbourhoods were targeted for disinfecting and waste removal, including Millers Point, around Darling Harbour, and sectors of Glebe and Chippendale. Beginning 23 March 1900 and under the authority of George McCredie, houses, streets and drains were scrubbed with a mixture of noxious fluids: lime chloride, carbolic water (diluted phenol), sulphuric acid and calcium hypochlorite.

Almost 53,000 tons of garbage was collected and either incinerated or dumped at sea.

Widespread vaccinations were also introduced. On 24 March 1900, the Herald reported: “About 2500 persons were inoculated with prophylactic yesterday in order to be protected against infection from the plague. A staff of 14 medical men was engaged throughout the day… Dr. Armstrong, of the Board of Health, attended at the Town Hall yesterday and inoculated a number of the officials with prophylactic serum. The remainder of the council's employees will be inoculated in a few days…”

Cross-harbour ferries were strictly monitored. The 24 March Herald article stated, “The ferry steamers plying between Darling Harbour and the suburbs are being disinfected under the direction of the health authorities.

“A proclamation has been issued prohibiting masters of vessels from Sydney to local ports from making fast or landing goods or passengers at such ports unless they hold a certificate from the Board of Health declaring that their vessels have been properly fumigated.”

Compulsory purchase of properties

The NSW Govt compulsorily reclaimed ownership of almost the entire peninsula west of Sydney Cove, from Circular Quay to Darling Harbour, including The Rocks, Dawes Point and Millers Point.

This was formalised through the Darling Harbour Wharves Resumption Act 1900.

Approximately 900 privately-owned residential houses were purchased, in addition to wharves, workshops, warehouses, inns, offices and factories, costing around £2,000,000.

Controversially, containment of the plague was also used as justification to evict and destroy temporary dwellings all over the peninsula, from The Rocks and around the wharves to Pyrmont as well as east of the city in Paddington. These ranged from shanty-town slums consisting of corrugated iron sheets and timber, to converted horse stables and backyard sheds.

The impoverished occupants, many of whom were unemployed or low-income dockworkers and labourers, had no legal right of appeal.

Authorities also demolished many small private jetties where ships were docking, sometimes covertly to evade customs and excise duties, in order to better consolidate and regulate the main wharves.

Sydney free from plague infection?

In September 1900, Health Authorities declared Sydney was free from infection, and the yellow flag indicating Sydney was a plague city was furled from the Quarantine Station on North Head, at the entrance to Sydney Harbour. 1,759 people were quarantined in the eight months of the epidemic, of which 263 tested positive to the plague.

During that time, a total of 303 cases were reported to authorities; ultimately, 103 people succumbed to the contagion – a 33% mortality rate, which was significantly lower than the 82% peak mortality rate reported during the 1896-97 Indian plague.

Although Dr Thompson oversaw the successful control of the 1900 bubonic plague contagion in Sydney, he was never rewarded for his research and skills, despite being acknowledged in the international scientific community. The Indian Plague Commission of 1905 praised his reports as 'models of cogent reasoning'.

His calm management also took place during the Boer War, the 1899-1902 conflict in South Africa fought between the British Empire and the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, in which 16,000 Australian troops participated.

Dr Thompson retired in 1913 and died in his home city of London in 1915.

A ‘second wave’ of the plague was recorded in both Brisbane and Sydney in 1902, then a third outbreak in Sydney was dealt with between May and August 1903.

Dr. Thompson, as Chief Medical Officer of the NSW Board of Health, continued to play a key role in managing the successive outbreaks and implementing strategies to control the spread of the disease. His team’s successful disinfection, quarantine and rat elimination tactics were again deployed. These included lockdowns, closures of public libraries and the disinfection of wharves, houses and public transport vehicles and vessels.

On 8 March 1902, the Sydney Advertiser revealed, “a combined attack on the rats was made by the various governing and health authorities of the city and suburbs. Many thousands of packets of poison were distributed to private people beforehand by the City Council, and elaborate preparations were made. Refuse was destroyed so that the rats would be starved into taking the poison…

“Shipmasters are being fined for failing to attach metal discs to the mooring lines of their vessels, so as to prevent rats going along them….”

Smaller outbreaks of plague return to Sydney

Between 1900 and 1925, there were 12 major plague outbreaks across Australia. The primary sources of contagion were ships bringing infected sailors, new immigrants and of course, rats. During that era, the first quarter century of Australia’s federation as an independent nation, official health archives recorded 1371 plague cases resulting in 535 deaths, the majority in Sydney (although there were smaller outbreaks in Melbourne and Adelaide and remote regions too, including northern Queensland and Fremantle in Western Australia). In total, 1,371 cases were reported across Australia, with 535 fatalities.

The official Bubonic Plague Register for Sydney, covering the years 1900-1908 when the city was repeatedly impacted, was subjected to a 110-year embargo preventing its publication. This was enacted so as not to stigmatise those infected – 608 cases. That embargo expired in February 2019 and the data on the individuals affected - who, where, when and their occupation - is now publicly accessible.

Marrickville infections

Beyond the crowded dockside slums of central Sydney and The Rocks region, plague was reported further afield, including Marrickville, 11km from the epicentre of the harbour wharves.

On Saturday 24 March 1900, The Sydney Morning Herald newspaper reported that a Marrickville resident was infected with the bubonic plague.

“William Hayden, 21, living at Marrickville, was found to be suffering from bubonic plague yesterday, and was, with nine other residents of the house, removed to the Quarantine Station.”

Two years later, another Marrickville resident who caught the disease during the ‘second wave’ of the plague was afflicted while working in an affected zone. An 8 March 1902 report in the Sydney Advertiser, said, “Minnie Boardman, tailoress, aged 21, residing at Petersham road, Marrickville, but working in the infected area in Pitt street, near Market street, one of the areas being cleaned by the council were reported.”

A victim of one of the later plague outbreaks, Ethel Williams, was only 21 years of age when she died on 31 December 1907. Her occupation was not listed in the official Plague Register archive, but she resided at 35 Thomas St Marrickville.

Another six years later, in a single paragraph dated 8 January 1908, The Dubbo Despatch reported on a case of Plague Rats found in Marrickville. “Seventy six dead rats have been found under the floors of the Marrickville produce store to which the two cases of plague were traced – nineteen being poison-infected.”

=================================

Comments