Early History of Randwick

- Nov 25, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2025

The history, origins, settlement and early development of Randwick, from colonisation to city status.

By ALEC SMART

Randwick, located 6km east of Sydney central business district in the Eastern Suburbs, was proclaimed as a Municipality on 22 February 1859 – the second oldest Local Government Area in NSW after City of Sydney - and contains at least 15 historic properties listed with NSW State Heritage Register.

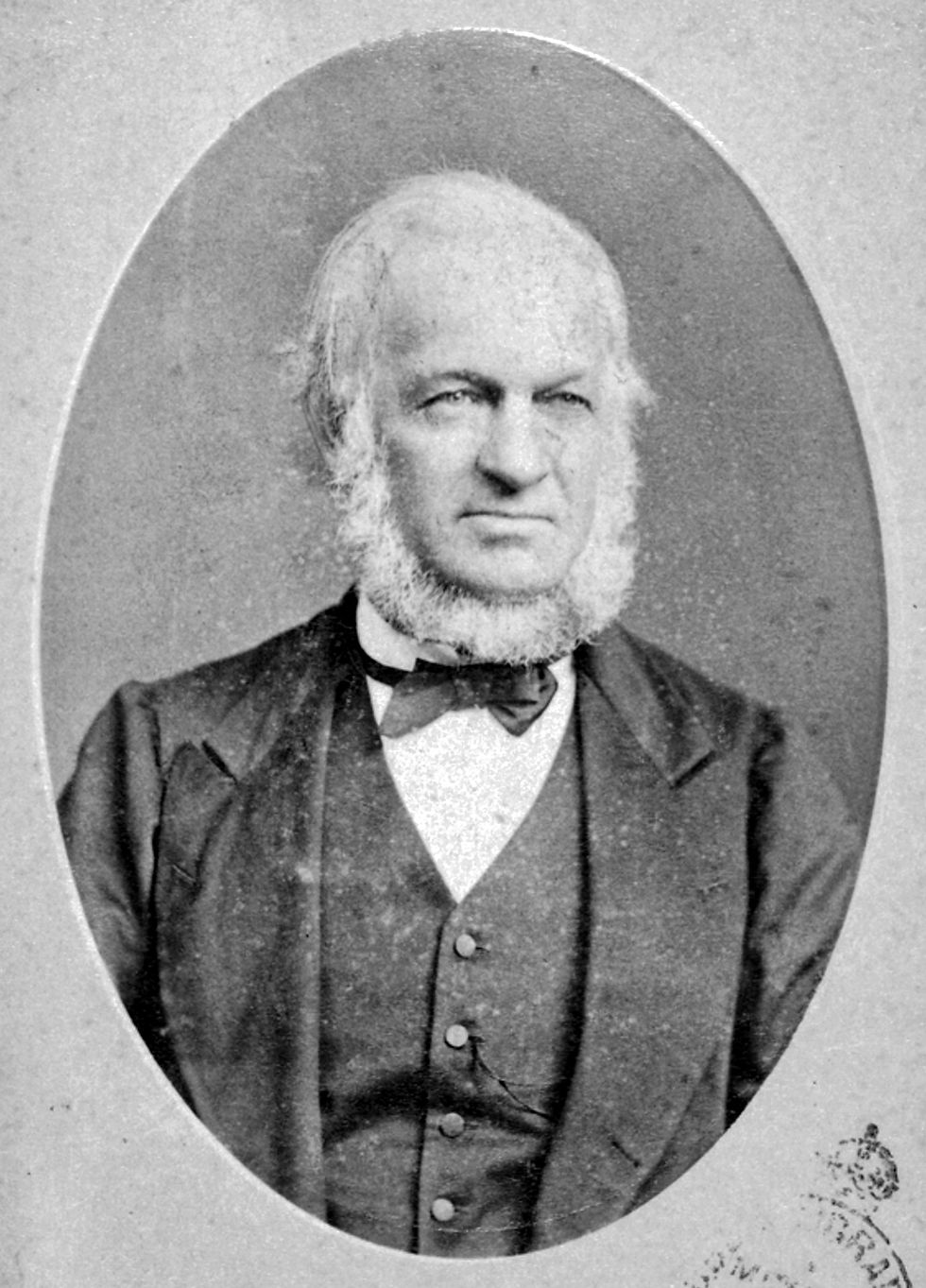

Diving into the history of Randwick, we discover that the name ‘Randwick’ was derived from a property owned by Simeon Henry Pearce, an English surveyor who arrived in Australia in 1841, aged 21, with his cousin Samuel.

In 1844 Pearce purchased a small 4-acre plot in the area then-known as Coogee Hills from landholder Captain Francis Marsh. The region was, at the time, dominated by market gardeners, who took advantage of the fertile soil after the forests were felled and the land subdivided.

Pearce called his property ‘Randwick’ after the Gloucestershire village in south-western England where he grew up. The English Randwick is only a small village bordering the market town of Stroud. It’s probably best-known for the ‘Randwick Wap’, an ancient Spring festival featuring costume parades, festivities and a ceremonial ‘cheese rolling’ of big wheels of Gloucestershire cheese around the churchyard. Founded in the Middle Ages, in 1892 the Wap was suspended after it became renowned for drunken revelry, but in 1971 it was revived.

Pearce built a sandstone cottage, Blenheim House on his property, facing the old Sandy Track racecourse (founded 1833, which eventually became Randwick Racecourse, despite Pearce’s objections, after the Australian Jockey Club relocated there in 1860). The historic house still stands today at 17 Blenheim St, Randwick, set back from the road and behind a timber fence, and has recently been converted into a multi-purpose arts and culture centre.

Pearce and his brother James were responsible for the founding and early development of Randwick and the neighbouring Coogee district. This included buying and selling property and overseeing the construction of a road from the city to Coogee in 1853.

By 1854 Pearce had purchased 200 acres of land on the Northern Beaches and 200+ acres in Randwick and the St George district, which were subdivided and sold.

Simeon Pearce was also Randwick Council’s inaugural Mayor and served six terms between April 1859 and February 1883.

Randwick, pre-urbanisation

But prior to the Pearce brothers’ municipal guidance, what was the area like as the first European settlers arrived?

According to the Randwick Council’s Heritage Study (2021), “Coogee was known as ‘Great Coogee’ during the early 1800s and Coogee Bay was a seaside attraction from as early as 1820. The village of Coogee was officially founded 12 October 1838 [with a] planned grid of intersecting streets…

“[In] the early days of European settlement, Coogee flourished as a market gardeners’ paradise. Many of the first residents… made their fortune growing vegetables for the Sydney markets and large mansions were being built.”

A NSW Dept Environment report states, “Randwick was... slow to progress. The village was isolated from Sydney by swamps and sandhills, and although a horse-bus was operated by a man named Grice from the late 1850s, the journey was more a test of nerves than a pleasure jaunt. Wind blew sand over the track, and the bus sometimes became bogged, so that passengers had to get out and push it free.”

The report continues, “From its early days Randwick had a divided society. The wealthy lived elegantly in large houses built when Pearce promoted Randwick and Coogee as a fashionable area. But the market gardens, orchards and piggeries that continued alongside the large estates were the lot of the working class. Even on the later estates that became racing empires, many jockeys and stable-hands lived in huts or even under canvas.

“An even poorer group were the immigrants who existed on the periphery of Randwick in a place called Irishtown, in the area now known as The Spot, around the junction of St.Paul's Street and Perouse Road. Here families lived in makeshift houses, taking on the most menial tasks in their struggle to survive.”

Original Aboriginals

Randwick town centre is just 2km from the South Pacific Ocean in Coogee Bay. Coogee (gazetted as a village in 1838) is believed to derive from the Indigenous Dharug word ‘kooja’, which referred to the pungent smell of kelp washed up on the beach rotting in the sun.

The Indigenous peoples of the area were principally the Gadigal. They occupied most of the region south of Sydney Harbour, and west to Darling Harbour and the lower tidelands of the Parramatta River and southwest to Goolay'yari/Cooks River.

There were also smaller clans resident along Sydney’s south-eastern shores: the Birrabirragals on South Head, around what is now Camp Cove, Kutti/Watsons Bay and Bondi Beach; the Muru-ora-dial, who inhabited the coastal region from Maroubra south to Malabar and around the north shore of Kamay/Botany Bay; and the Bidjigal, who inhabited the region north of Kamay/Botany Bay and inland to Salt Pan Creek and the estuarine areas north of Tucoerah/Georges River.

When the First Fleet arrived in 1788, the Aboriginal population in the greater Sydney region was somewhere between 1500 (Governor Phillip’s guesstimate of those within a 10-mile radius of Port Jackson) and 8000.

The clans would have traded, socialised, shared ceremonies, sourced the same food, and inter-married, and they all spoke the same language – Dharug, albeit with several dialects. They are now known as people of the Eora Nation.

The Eora hunted in the bushland - primarily eucalyptus woodlands and sclerophyll forests (characterised by hard-leaved evergreen trees and undergrowth) - fished in the seas from nowie (bark canoes), and gathered shellfish and speared marine creatures along the foreshore.

The Eora of the coastal region were described as katungal - ‘sea people’ – by the paienbera ‘tomahawk people’ inland (who hunted and trapped animals), because they were primarily reliant on marine food sourced from the harbour, beaches, tidal rivers and estuaries.

Displacement and Death

Sadly, the Indigenous peoples were displaced by the British after their arrival in 1788 to set up a penal colony, either driven inland or killed in confrontations with the gun-wielding invaders. Many Aboriginals succumbed to European diseases due to their reduced immunity, especially the devastating smallpox epidemic of 1789. The latter was likely deliberately started by Royal Marines, gifting infected blankets to an Aboriginal campsite at Balmoral Cove.

However, there is still plenty of evidence of their existence across Sydney metropolitan area and especially along the coast, including fading rock engravings and hand stencils, axe-sharpening grooves in favoured rocks, shell middens (piles of scrap shells on foreshores) and scarred old trees from which bark was extracted for canoes.

The Dharug word ‘Bobroi’ may have been the name for the region encompassing what is now Randwick, Coogee and Clovelly to the north, but British settlers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries weren’t in the habit of asking the locals the place names of the areas they were colonising.

The British administrators were, however, in the habit of giving land grants to favoured people, including distinguished former convicts whose skills were useful to the expanding colony, and high-ranking military personnel.

The Royal Marines, the first garrison of colonial-era Australia (1788-90), succeeded by the New South Wales Corps (1790 – 1818), were recipients of huge tracts of land, many of which were traded, sold and sub-divided.

After the first Governor Arthur Phillip returned to Britain in 1792 due to ill-health, Major Francis Grose effectively transformed the penal colony into a military dictatorship.

He cut food rations to convicts and gave generous land grants to officers of the Corps – who by 1793 were known as the ‘Rum Corps’. This was because they gained a monopoly over imported rum, which they used as currency to make up for the shortage of minted coins, and further diverted vital grain supplies from food to the brewing of rum.

Although successive governors – John Hunter, Phillip King, William Bligh – tried to diminish the power of the NSW ‘Rum’ Corps, they were thwarted and English courts 17,000km away effectively powerless. An 1808 coup d'état, the ‘Rum Rebellion’, backed by wealthy agri-baron John Macarthur, ousted Governor Bligh and placed him under house arrest.

Eventually, the mutinous New South Wales Corps, renamed the 102nd Regiment of Foot, were recalled to England and replaced with the 73rd (Perthshire) Regiment of Foot, whose commanding officer, Lachlan Macquarie, took over as NSW Governor.

It wasn’t until Governor Lachlan Macquarie assumed power (1810-21) that some sort of order was maintained and the rum economy regulated.

One of the first land grants in the Randwick region was made – unsurprisingly – to a military commander, Captain Francis Marsh, an officer of Her Majesty's 80th Regiment of Foot.

In 1824 he received 4.9 hectares (12 acres) of land in what is now within the boundaries of Botany and High Streets and Alison and Belmore Roads.

Marsh later subdivided his estate and one parcel of land he sold to the aforementioned Simeon Henry Pearce.

Randwick was not proclaimed a City until 1990, which included 10 beaches and bays from Clovelly in the north to La Perouse in the south, and the suburbs Chifley, Clovelly, Coogee, Kensington, Kingsford, La Perouse, Little Bay, Malabar, Maroubra, Matraville, Phillip Bay, Port Botany, Randwick, and South Coogee and most of Centennial Park.

=================================

Comments